Interview

“Without climate change, there would be fewer conflicts in the Arctic.”

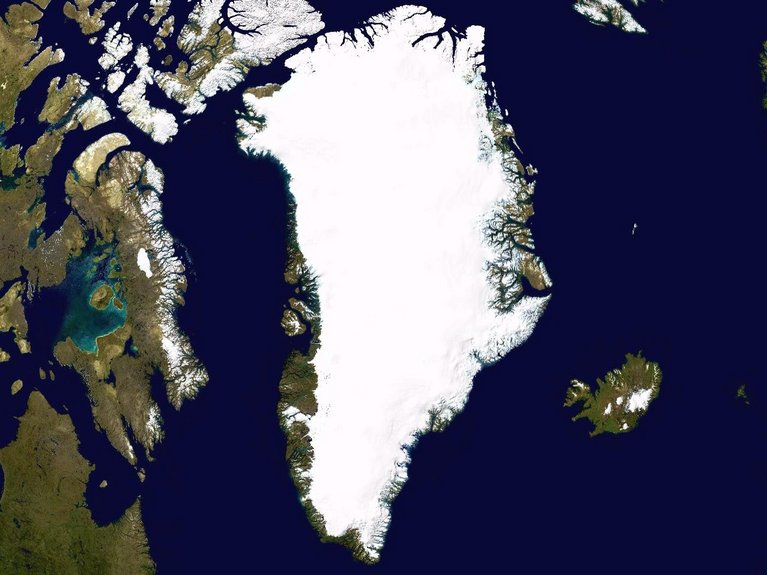

Satellite image of Greenland, Iceland, and the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Image: NASA / Ames Research Center (public domain, via Wikipedia)

After three decades of relative stability, tensions in the Arctic are escalating. What strategic objectives are the actors in the High North pursuing? How does the German Arctic Office assess the situation in Greenland? And what role can science play in diplomacy? An interview with Arctic expert Volker Rachold, AWI.

Volker Rachold is Head of the German Arctic Office at the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research. The office advises the German government on Arctic affairs and disseminates information from scientific research. A geochemist by training, Rachold also supports the Federal Foreign Office, which represents Germany as an observer in the Arctic Council.

Mr. Rachold, where does the interest in Greenland originate? What makes the country so geopolitically significant?

Interest in Greenland and the wider Arctic region arises from a combination of strategic, economic, and scientific considerations, which are being further intensified by climate change. The retreat of sea ice is opening new maritime routes, improving access to natural resources, and increasing geopolitical competition. U.S. President Donald Trump has argued that the United States already possesses extensive military rights in Greenland, including the ability to reinforce troops, establish military installations, and monitor and control the movement of ships and aircraft. These rights are guaranteed under the 1951 Thule Agreement between the United States and Denmark. The security argument is therefore likely to serve as a pretext, similar to claims that Chinese or Russian vessels are operating off Greenland with hostile intent. Such assertions are not supported by evidence; if anything, Russian and Chinese naval activity is more commonly observed in the vicinity of Alaska. Moreover, the argument that Greenland must be secured to prevent Russia from becoming a direct neighbor is unconvincing. A look at the world map makes clear that Russia has been geographically close to the United States for more than 150 years—the Bering Strait, separating Alaska from Russia, is narrow enough to be crossed by swimming.

So what are his real interests?

One key factor is likely greenland's natural resources, particularly rare earth elements. Access to these materials is strategically important, as China currently dominates the global market for rare earths. In addition, there is interest in Greenland's potential hydrocarbon resources, including oil reserves believed to exist beneath the ground.

Would it be so easy to extract it in Greenland?

No, not at all. On the one hand, the island lacks the necessary infrastructure, such as roads and ports. On the other hand, extraction is also extremely challenging from a techical perspective. After all, this is the Arctic. Most importantly, however, such plans face strong opposition from the Greenlandic population itself. In 2021, Greenland's government banned all oil and gas exploration and production in order to protect the environment and climate. Nature conservation plays a central role in Greenlandic society. A large share of the population belongs to Indigenous communities that have adapted to living in close harmony with nature over thousands of years.

What do you hear from the people there? Are they mainly worried or angry?

I hear both, but above all, astonishment at the sudden international interest in their island. Relations with Denmark are also not without tension, largely due to a complex colonial history. Many Greenlanders would prefer full independence. However, opinion polls clearly show that, when faced with this choice, around 85 percent of the population would rather remain part of Denmark than join the United States.

Volker Rachold is Head of the German Arctic Office at the Alfred Wegener Institute. Image: Jan Pauls

The situation in Greenland, and more broadly in the Arctic, is extremely tense—after years during which the region had largely remained insulated from global conflicts.

That is correct: for many years, the Arctic was a region exemplifying peaceful cooperation among different nations. There is even a term for this: Arctic exceptionalism. However, this changed following Russia's attack on Ukraine. Today, the Arctic resembles a situation similar to that of the Cold War. At that time, the nuclear submarines of the Soviet Union and the United States were hidden beneath the Arctic ice. It was Mikhail Gorbachev who changed this dynamic with his 1987 speech in Murmansk. In it, he proposed cooperation on three key Arctic issues: disarmament, environmental protection, and scientific research. This speech also paved the way for the establishment of the Arctic Council, which remains the leading forum for collaboration on environmental protection and sustainable development in the Arctic. Furthermore, the International Arctic Science Committee, a central organization in global polar research, was established. Research at the Alfred Wegener Institute, which had previously focused more on Antarctica, also began to increasingly concentrate on the Arctic. The German Arctic Office at AWI was established in 2017 to serve as a liaison between scientific research and policy.

China is also involved in Arctic research. To what extent does this involvement stem from the country’s interest in exploring northern sea routes that may become navigable in the future due to the retreat of Arctic sea ice?

The Arctic Sea routes are strategically important for all major trading nations, primarily Russia. The passage along Russia’s northern coast significantly shortens the maritime journey between Europe and Asia. However, the route is currently used less than expected, partly because of international sanctions. Currently, it is mainly Russian and Chinese vessels that navigate these waters. There is no doubt that access to this shipping corridor is one of the key factors motivating China’s engagement in Arctic research. In 2009, China even formally declared itself a near-Arctic state, despite being approximately 1,500 kilometers from the Arctic region.

But do you see a direct threat to Greenland?

Not at all —not even from Russia. China has sought to increase its influence on the island, primarily due to its interest in Greenland’s natural resources. However, these efforts have not been successful, as the Greenlandic population has clearly rejected such initiatives. Neither Russia nor China has made statements comparable to those expressed by U.S. President Donald Trump in recent weeks.

Nevertheless, we are transfixed by this conflict. Does this risk distract from the central issue facing the Arctic—namely, climate change?

Other issues are indeed moving increasingly to the forefront, including in German Arctic policy. This shift is clearly reflected in Germany’s Arctic policy guidelines. The previous version, published in 2019, placed a strong emphasis on environmental and climate protection. By contrast, the current version from 2024 is primarily focused on security policy. At the same time, international interest in the Arctic’s natural resources is growing. Norway, for example, is identifying new oil fields in the Arctic, while in Alaska, former U.S. president Joe Biden approved highly controversial drilling projects. Like Russia, these countries play an ambivalent role: they are members of the Arctic Council, which is committed to protecting the Arctic, yet they continue to extract oil and gas in the region. Such activities not only exacerbate climate change but also pose a significant environmental risk. An oil spill in the Arctic would have far more severe consequences than in other regions, as oil cannot be effectively contained by barriers due to ice coverage. In addition, low temperatures cause oil to degrade extremely slowly.

So we need to be concerned not only with security in the Arctic, but also increasingly with environmental concerns.

These aspects are difficult to separate. Without climate change, there would be fewer conflicts, as the Arctic’s natural resources would remain largely inaccessible and most sea routes would be impassable. This makes Donald Trump’s argument all the more striking: he denies the existence of climate change, yet at the same time seeks access to Arctic resources—fully aware that it is climate change that makes these resources accessible in the first place.

In this situation, could Arctic research once again become a symbol of peaceful coexistence?

I hope so —but patience will be required. The next Polar Year (2032/33) could provide a significant impetus. These international research programs take place at regular intervals and have repeatedly influenced political developments in the past. One notable outcome of the Third International Polar Year in 1957/58 was the Antarctic Treaty, which guarantees peaceful cooperation at the South Pole. For such progress to occur again, however, political will would be required from all parties involved—and unfortunately, I do not currently see that. And yet, only six years ago, the Arctic states jointly supported the large-scale MOSAiC expedition. During that mission, our research icebreaker Polarstern drifted through the Arctic ice for an entire year. The expedition was led by the AWI, but it was only possible because many other countries participated—most notably Russia and China. A project of this kind would be unthinkable today. At the time, we faced unexpected challenges due to the coronavirus-related restrictions, and at one point, it was even unclear whether the expedition would have to be abandoned. Ultimately, however, Russia provided assistance with its icebreakers. That was only six years ago, yet it feels like a long time ago. The question now is whether we can return to that level of cooperation—or whether this form of cooperation is a thing of the past.

Readers comments