Comet hunter Rosetta

Time of awakening

Photo: DLR (CC-BY 3.0)

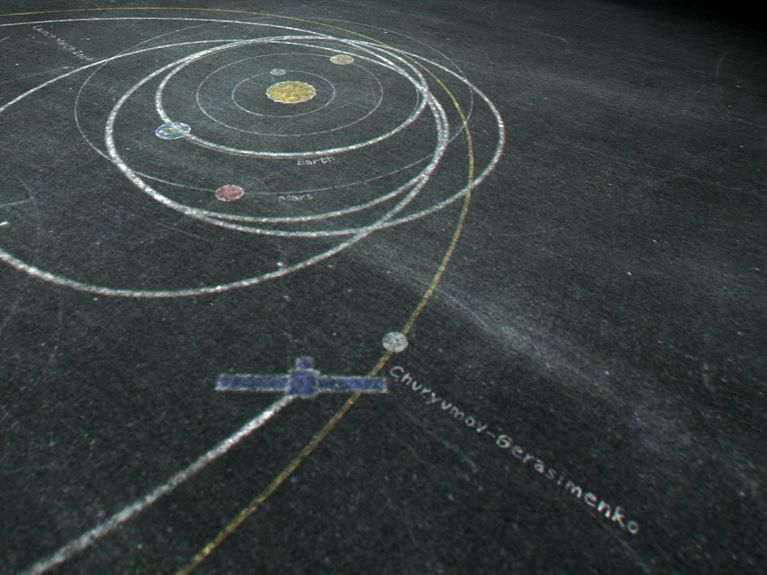

In November, for the first time ever and after a ten-year flight through our solar system, travelling more than seven billion kilometres, a spacecraft is scheduled to accompany a comet for a longer term and to set down a landing unit. On 20th January it awakened as planned from an energy-saving hibernation mode: a key moment in the entire mission

This year, after ten years of travelling through our solar system and brief encounters with the asteroids Šteins and Lutetia, the spacecraft Rosetta is scheduled to reach its actual target: the comet Churyumov–Gerasimenko. In November, a landing unit the size of a fridge is to land on the comet. This would be the first landing on a comet ever. The scientists at the European Space Agency (ESA) will then have the opportunity of finding out more about these celestial objects, which are considered to be witnesses of the origins of our solar system. The mission, the cost of which totals one billion Euro, is designed to provide answers to questions such as whether water and organic compounds were introduced to Earth via comets. "It may well be that comets constitute the key to the origins of life", says Stephan Ulamec from the German Aerospace Center (DLR).

To make sure that it reaches the comet at the precise moment in its orbit that is most ideal for the mission and with the required speed, Rosetta had to travel a total of seven billion kilometres. The spacecraft gathered momentum during three flybys of Earth and one flyby of Mars before it disappeared into the depths of the solar system. These past 957 days, Rosetta continued its journey along the designated trajectory whilst in energy-saving standby mode. This hibernation mode was necessary because the spacecraft had travelled very far from the sun. The energy provided by the solar panels was just enough to heat up the space probe a little and to keep the highly sensitive equipment from cold-induced total damage. Normal operation was not possible.

On 20th January, at ten in in the morning Central European Time (CET), the probe awakened from its hibernation mode – in approximately 800 million kilometres distance from Earth. A time switch triggered a series of internal commands. At the end of this command cascade, the main antennae sent a signal to Earth. The cheering was accordingly loud at the ESOC (European Space Operations Centre) in Darmstadt, the ESA's control centre, when at 19:18 hours CET the first signal from Rosetta in 2.5 years appeared on the monitors.

Rosetta's path through our solar system

After waking up, the spacecraft is intended to target Churyumov–Gerasimenko and enter the final stage of its journey. At this point it is still nine million kilometres away from its destination. Rosetta and the comet, which is on a wide trajectory through our solar system, are scheduled to meet in August. At first, the space probe will enter into a controlled orbit around the only roughly four kilometre large celestial object and will send first images of the surface to Earth. The mission's highlight will then follow in November: the comet lander Philae, carried on the back of the space probe, is scheduled to land on the comet.

The landing has been planned and will be controlled by the German Aerospace Center (DLR). On site at the DLR, a replica of the landing unit had to endure a lot: scientists and engineers have tested the landing under various conditions. After all, nobody knows exactly what the surface condition of the comet will be like. From soft snow to hard ice – anything is possible. In the landing process, Philae will shoot two harpoons, which will serve as anchors, into the substratum. Because of the comet's low gravity, the landing unit will be hardly any heavier than a sheet of paper, whereas on Earth it weighs a hefty 100 kilograms. Since the lander will not bring any specimens back to Earth, it contains a small laboratory, which will carry out analyses on site, sending the data to Earth. The DLR carries the main responsibility for three of the altogether ten instruments.

The comet will then continue to move towards the Sun, accompanied by Rosetta. The increasing temperature during the approach to the Sun causes every comet to lose gases and dust from its core, which are torn away by the solar wind. This creates the typical tail. The entire event will be investigated by Rosetta and the lander secured to the surface of the comet. It is by no means safe to say that Philae will survive all this and will be able to carry out its tasks as planned. This is going to be an exciting time for the scientists. Time to wake up!

Readers comments