Natural resources

Mining in the deep ocean

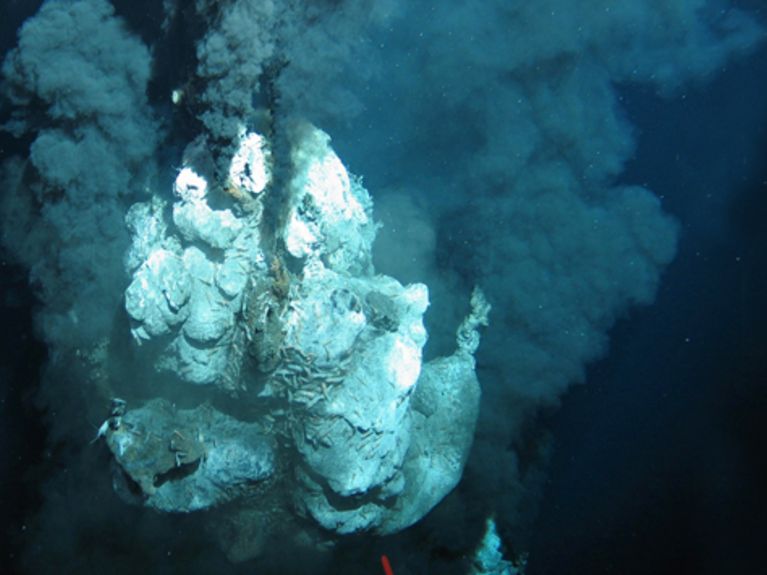

Release metals from the deep: black smokers were given their name due to their similarity with industrial chimneys. Photo: ROV-Team / Geomar

A treasure lies buried in the sea bed. Not a pirate's bounty, no sunken ship – this is about manganese nodules, cobalt-rich crusts and massive sulphide deposits that are found in several kilometres depth. Should we lift this treasure?

Pedants, pay attention: we are getting precise down to the atom! Take a rock sample of only one billionth gramme, examine it with a so-called Vast amounts of valuable raw materials are deposited deep in the ocean. Rocks that are millions of years old contain metals that fetch several billion Euro. This has been well known for decades. Yet the treasure remains deposited on the sea bed in spite of numerous countries showing interest, in spite of advanced technology and in spite of an increasing demand for raw materials. This is good news for research: more time to find answers to important questions. For example, how could the valuable metals be extracted and brought to the surface without harming the marine ecosystem? How could risks to the environment be better assessed? Not only international research projects play a role in answering these questions, but also a small deep sea mussel – more about this later.

First, the facts: the fist-sized manganese nodules weighing about one pound are located in 5,000 to 6,000 metres depth and consist mainly of manganese and iron oxides. Their copper, nickel and cobalt content makes them interesting for the electronic and stainless steel industry. Layer by layer, the metals that are dissolved in the seawater deposit around crystallisation cores. They have been doing this for a long time: the diameter of a manganese nodule grows by 10 to 20 millimetres in one million years. The largest deposits are located in the North-East Pacific Ocean, where in some parts half of the seabed is covered by these nodules. Whilst the cobalt-rich crust and massive sulphide deposits usually belong to island states, the manganese nodules are mainly located in international territory beyond the 200-nautical-mile zone, the exclusive economic zone. To prevent a Wild West style run on the best claims, the licences for extracting deep sea natural resources are issued for 15 years by the International Seabed Authority, headquartered in Kingston, Jamaica. This authority has been governing the deep sea raw materials on behalf of the United Nations since 1994 as a joint heritage of mankind. To apply for a licensed area of 75,000 square kilometres – a little more than the territory of Bavaria – the applicant has to previously prospect an area twice that size, that is, take ground samples, record marine life forms. This takes several years. The IMB then selects one half of this total area and allocates it free of charge to developing countries for further exploration.

First, the facts: the fist-sized manganese nodules weighing about one pound are located in 5,000 to 6,000 metres depth and consist mainly of manganese and iron oxides. Their copper, nickel and cobalt content makes them interesting for the electronic and stainless steel industry. Layer by layer, the metals that are dissolved in the seawater deposit around crystallisation cores. They have been doing this for a long time: the diameter of a manganese nodule grows by 10 to 20 millimetres in one million years. The largest deposits are located in the North-East Pacific Ocean, where in some parts half of the seabed is covered by these nodules. Whilst the cobalt-rich crust and massive sulphide deposits usually belong to island states, the manganese nodules are mainly located in international territory beyond the 200-nautical-mile zone, the exclusive economic zone. To prevent a Wild West style run on the best claims, the licences for extracting deep sea natural resources are issued for 15 years by the International Seabed Authority, headquartered in Kingston, Jamaica. This authority has been governing the deep sea raw materials on behalf of the United Nations since 1994 as a joint heritage of mankind. To apply for a licensed area of 75,000 square kilometres – a little more than the territory of Bavaria – the applicant has to previously prospect an area twice that size, that is, take ground samples, record marine life forms. This takes several years. The IMB then selects one half of this total area and allocates it free of charge to developing countries for further exploration.

Nodule harvest in the deep ocean: collectors like this could pick up manganese nodules from the sea bed in future. Image: Anker Solutions

The German licence area for manganese nodules lies in the Clarion Clipperton Zone, a section of the ocean between Mexico and Hawaii. "The nodule density there is between 15 and 30 kilogramme per square metre; the average is about 20 kilogramme", explains Carsten Rühlemann, marine geologist and head of exploration at the Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources. The neighbours: the United Kingdom, Poland, Belgium, South Korea, France, Russia – a total of 17 countries have claims here. The Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources in Hanover has been exploring the German claim since 2006 and applied for an exploration licence for massive sulphide deposits in late 2013.

The researchers from the GEOMAR – Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel mostly focus on environmental risks. After all, the probability of commercial extraction of the deep sea raw materials is increasing. As early as in 1978, the prototype of a "harvesting machine" owned by an international syndicate did a test run, collecting manganese nodules very much like a potato harvester. At the time, the equipment could not be operated economically, yet with today's know-how this would be feasible for a successor. Also, the demand for raw materials increases due to emerging countries such as China and India. At the GEOMAR, researchers are well aware of the value of the deep sea raw materials. However, their extraction could result in a veritable "dust storm" in the Pacific Ocean, which, according to GEOMAR Director Peter Herzig, "is hardly likely to be beneficial for the ecosystem". "We see a big problem in the stirring up of sediments, which are not like our silt and coastal mud. These are mostly unhardened sediments with very fine particles." Combined with the continuous West-East deep water currents, this aforementioned storm would break loose, which could bury sensitive marine animals or at least considerably damage them. If the manganese nodules are hauled up aboard the recovery ship by way of a kind of vacuum cleaner system, this would suck up also sediments, which would have to be reintroduced, further increasing the dust storm. An unsolved problem then as it is today.

Yet another reason why a potential potato harvester has not yet been deployed on an industrial scale lies in the fact that such a device would have to withstand the water pressure at a depth of up to 6,000 metres and would have to reliably operate at one degree above freezing point. "South Korea is the technologically most advanced licensee and technically far ahead when it comes to extracting the nodules", says Carsten Rühlemann. "A South Korean collector has been successfully tested in 1,400 metres depth; a test in 5,000 metres depth is scheduled for 2016. When it comes to dressing the metals contained in the nodules, India is most likely to have a process that can be used on an industrial scale." Germany is lacking a major company that paves the way: "We no longer have a major mining corporation and the small ones are afraid of the high financial risk. After all, some 800 million Euro are required for an extraction system including metallurgic processing plant, plus 250 million Euro annual operating costs."

The researchers from the GEOMAR – Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel mostly focus on environmental risks. After all, the probability of commercial extraction of the deep sea raw materials is increasing. As early as in 1978, the prototype of a "harvesting machine" owned by an international syndicate did a test run, collecting manganese nodules very much like a potato harvester. At the time, the equipment could not be operated economically, yet with today's know-how this would be feasible for a successor. Also, the demand for raw materials increases due to emerging countries such as China and India. At the GEOMAR, researchers are well aware of the value of the deep sea raw materials. However, their extraction could result in a veritable "dust storm" in the Pacific Ocean, which, according to GEOMAR Director Peter Herzig, "is hardly likely to be beneficial for the ecosystem". "We see a big problem in the stirring up of sediments, which are not like our silt and coastal mud. These are mostly unhardened sediments with very fine particles." Combined with the continuous West-East deep water currents, this aforementioned storm would break loose, which could bury sensitive marine animals or at least considerably damage them. If the manganese nodules are hauled up aboard the recovery ship by way of a kind of vacuum cleaner system, this would suck up also sediments, which would have to be reintroduced, further increasing the dust storm. An unsolved problem then as it is today.

Yet another reason why a potential potato harvester has not yet been deployed on an industrial scale lies in the fact that such a device would have to withstand the water pressure at a depth of up to 6,000 metres and would have to reliably operate at one degree above freezing point. "South Korea is the technologically most advanced licensee and technically far ahead when it comes to extracting the nodules", says Carsten Rühlemann. "A South Korean collector has been successfully tested in 1,400 metres depth; a test in 5,000 metres depth is scheduled for 2016. When it comes to dressing the metals contained in the nodules, India is most likely to have a process that can be used on an industrial scale." Germany is lacking a major company that paves the way: "We no longer have a major mining corporation and the small ones are afraid of the high financial risk. After all, some 800 million Euro are required for an extraction system including metallurgic processing plant, plus 250 million Euro annual operating costs."

Peter Herzig, GEOMAR director. Photo: Jan Steffen

It can be assumed that, should the industrial mining of deep sea raw materials become a reality one day, the manganese nodules will be the easiest job in the game – they "only" need to be picked up. By contrast, the cobalt-rich crusts are firmly connected to the substrate rock. They are mostly found in the western Central Pacific Ocean and contain cobalt, nickel, manganese, titan, copper and cerium as well as trace metals such as platinum, molybdenum, tellurium and tungsten. The massive sulphide deposits in 3,000 to 4,000 metres depth are of volcanic origin and occur at active and extinct black smokers – hydrothermal vents, where up to 400 degree Celsius hot water issues from the ocean bed. In the process, sulphides precipitate and form deposits of several hundred metres in diameter. They contain copper, lead and zinc as well as gold, silver and high technology metals such as indium, germanium, bismuth and selenium. GEOMAR Director Peter Herzig assesses the extraction of these metal ores as far less problematic: "Here, mainly lava rock would be stirred up, which settles again much faster." 2.5 million metric tons metal sulphides are thought to lie off Papua New Guinea alone. "You could half fill the Berlin Olympic stadium with that amount", says Herzig. Estimated metal value: 2.2 billion Euro.

Actually, the entire ecosystem would have to be researched to assess the ecological consequences of exploiting all these raw materials, but that is very difficult in such great depths. This is where a small, really very unassuming mussel comes into play: Bathymodiolus childressi, a deep sea relative of our blue mussel. It lives in about 500 metres depth in cold seeps in the Gulf of Mexico and along the eastern coast of the USA. Marine researchers from the Kiel Marine Organism Culture Centre, a joint project of the GEOMAR and the Kiel-based excellence cluster "The Future Ocean", now have managed to keep it in aquariums. "Using computer models, we can understand where the mussel larvae drift to", says biologist Corinna Breusing from the HOSST graduate school, who is currently working on her PhD thesis at the GEOMAR under the supervision of Thorsten Reusch. "We can assess whether currents, fronts between the water masses or similar barriers prevent exchange between different populations."

A hand for mussels: Corinna Breusig researches deep sea mussels for her PhD thesis. Photo: J. Steffen / GEOMAR

The PhD student researches at the genetic level whether different populations can interbreed or whether certain reproduction mechanisms prevent this. According to Breusing, should it transpire that there is no connection between populations from different black smokers and that there cannot be one, meaning that the mussels and other organisms live in isolation from other habitats, this would mean: "If one extracts something at one smoker, the ecosystem is not only destroyed, but also it cannot regenerate because no new individuals from other habitats can settle there." The data derived from this exemplary work on Bathymodiolus childressi, which occurs only at cold seeps, is going to be used to create computer models that will approximate the species living at Central Atlantic seeps as far as possible. Yet in addition to all the ecological concerns, the mega project deep ocean mining harbours also an economic problem. Massive exploitation in the deep ocean could result in a general decline of raw material prices, which in turn would render the exploration inefficient. Marine geologist Carsten Rühlemann has done the maths and his conclusion: "One deep sea company is not likely to influence the world market. But the picture changes, if ten started at the same time."

Readers comments