Human Brain Project

"A key for further brain research"

Picture: Forschungszentrum Jülich

6oo million euro budget, 500 researchers involved, 3,000 publications: After ten years, the Human Brain Project is coming to an end. We spoke with the scientific director Katrin Amunts from Forschungszentrum Jülich about the balance sheet.

Ms. Amunts, this month marks the official end of the Human Brain Project after ten years. You have been at the helm of this flagship project of the European Union since 2016. What do you see as the key findings?

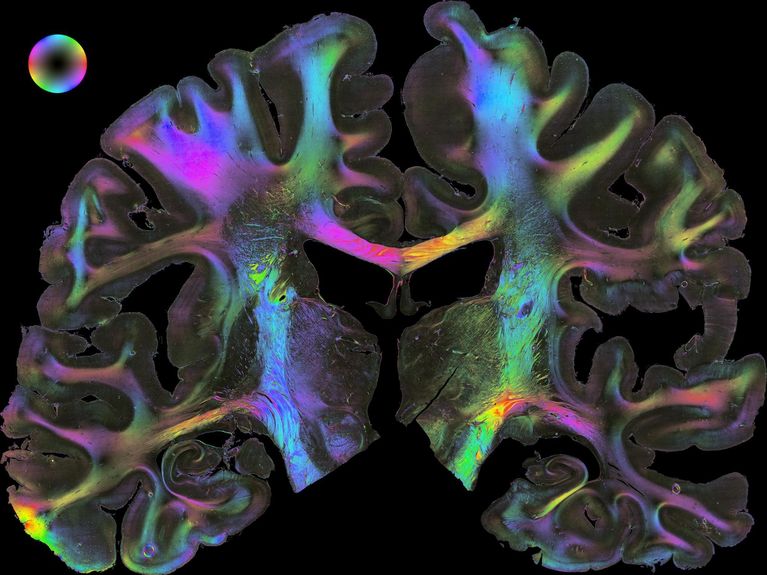

HBP researchers have achieved numerous scientific results that have been published in about 3000 papers. They have advanced medical and technical applications and developed or enhanced 160 freely available digital tools for neuroscience research. If I had to highlight something, it would be, for example, the multimodal atlas. It is already shaping research and will increasingly produce medical applications in the future, personalized simulation models of patient brains for medicine, or findings in consciousness research.

How should we imagine the atlas?

It is an atlas of the brain that not only reflects the anatomy down to the cellular level, but also links this to the connectivity structure, the molecular architecture of the brain and its function. Thus, the atlas depicts brain organization in a comprehensive manner. The atlas also links basic science to clinical application because, for example, it helps to better interpret imaging findings in patients. In the HBP, the atlas has an integrating role for different research approaches and directions, from neuroscience to cognition research, brain function modeling to clinical application.

What can you do with it?

The physician Katrin Amunts was scientific director of the Human Brain Project, a flagship project of the European Union, from 2016 to 2023. She is also director of the Institute for Neuroscience and Medicine (INM-1) at Forschungszentrum Jülich and director of the Cécile and Oskar Vogt Institute for Brain Research at the University Hospital Düsseldorf. Image: Maren Fischinger, Forschungszentrum Jülich

The atlas is fully accessible online and provides a kind of "Google Maps" of the brain. It is a basis for further systematic research on this organ, its mechanisms and its diseases. Our approach is that of a "living atlas" - we are constantly developing it, incorporating new findings. We also offer comprehensive support so that scientists can use it, there are tutorials, Youtube videos, introductory online seminars. And demand remains consistently high: The atlas has a huge impact on research, whether in China or the US.

What about advances in consciousness research?

Researchers at the Human Brain Project in Milan and Liège have been working on methods to measure consciousness. This involves measuring the brain response after brief magnetic stimulation and quantifying the complexity of this brain activity. It has been shown that this can be used to classify the level of consciousness. Knowing the state of consciousness has enormous implications for medical care of patients, for example, those in a coma, and for their relatives.

How do patients already benefit from the Human Brain Project?

Here, too, there are many examples. One important one is personalized brain models of patients using "The Virtual Brain" platform. This approach is currently being tested for epilepsy in a large clinical trial. The model processes measured data from the patient to help operators locate the regions from which seizures originate. It also provides predictions for the success of various surgical treatment strategies. The approach was presented this year in the journals Science Translational Medicine and The Lancet Neurology.

Picture: Maren Fischinger, Forschungszentrum Jülich

Another area is so-called neuro-stimulation: Fellow researchers in Lausanne, Switzerland, have developed an innovative spinal cord stimulation that enables patients to walk again after injury and paralysis. This is something that most researchers worldwide would not have thought possible just a few years ago. Colleagues from Amsterdam have developed so-called visual prostheses using a similar principle: These are electrode arrays that are inserted into the visual cortex in the brain and transmit signals from a camera to the visual cortex. They are to be used to enable people who have lost their ability to see, for example, due to retinal damage, to recognize objects and movements again. Such progress has only been possible because many disciplines are intertwined in the Human Brain Project: Neurology, basic research, artificial intelligence, computer simulations, technology.

Focusing on computer simulations: Are such personalized models something like a digital twin?

We would speak of a digital twin if we took the personalized model one step further. Digital twins have an increasing importance in medicine, but such a "twin" is not as similar to the original as it sounds, but instead helps to better understand a very specific context. A digital twin is therefore also a mathematical model. What makes it special compared to personalized models that already exist today is that, on the one hand, the model is constantly updated with new measurement data, and on the other hand, the model is continuously compared with its environment.

There has rarely been such a huge project in the history of European science. More than 500 participating researchers from more than 150 different institutions in 19 countries, a budget of more than 600 million euros. Is it even possible to manage something like this effectively?

The Flagship project was indeed something quite new in its size. On the one hand, we had to bring the researchers involved together, but on the other hand, we had to let them pursue their research in detail. We couldn't lose sight of the overarching framework of the project, but also had to give all the experts enough freedom. Managing all this was a huge challenge and a learning process over time. It wasn't always easy and straightforward, but even after stressful times with disputes, we learned from them after a while and continued to develop. For questions as complex as the human brain, such an approach is necessary and complements research in smaller consortia.

Now the Human Brain Project is officially over, will you disappear into a hole?

(Laughs) No, definitely not. For countless research projects, the Human Brain Project was a kind of starting point, and now it's a matter of picking up where we left off. Just last week, we completed a large, comprehensive proposal for the further development of EBRAINS, the research infrastructure that was established in the HBP. This will include further development of the atlas and, in particular, will be able to link it to clinical data from patients. There are several other projects in the making or just launched that are using and further developing the EBRAINS platform.

Readers comments