HELMHOLTZ extreme

A garden more than 5,000 metres under the ocean

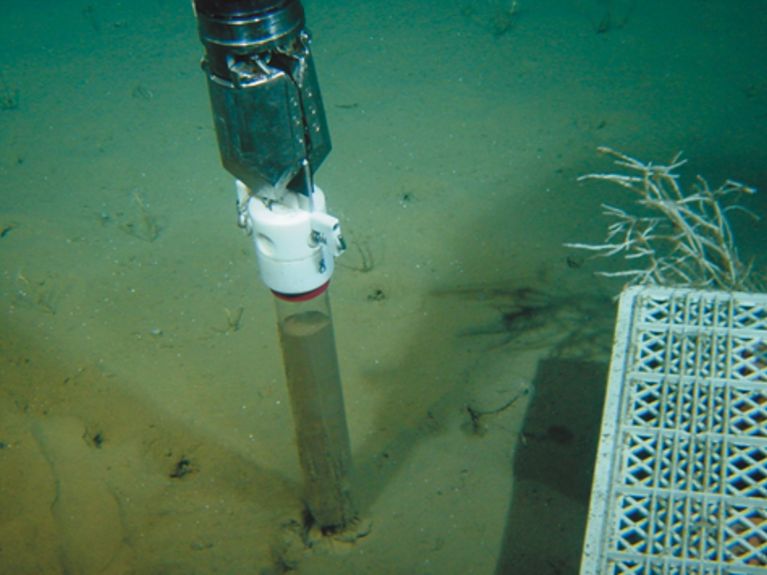

Photo: Michael Klages

When the scientists at the Alfred-Wegener-Institute talk about their HAUSGARTEN, they are not referring to the garden behind the Institute – they are talking about a multi-disciplinary observatory in the Arctic deep sea.

Dry deserts, ice-covered poles, tropical forests – the earth offers diversified and impressive landscapes. The largest one among them is the least well known – the deep sea. It covers more than 62% of the earth’s surface and is predominantly unexplored. Characteristic for this gigantic habitat under 800 metres of deep water are the extreme living and research conditions. Complete darkness and immense water pressure make it difficult for scientists to penetrate this habitat. Researchers even assumed for a long time that absolutely no forms of life existed at these depths. In 1860 when an attempt was made to carry out deep-sea repairs on a defective cable, strange animals were hanging on the cable retrieved from almost 2,000 meters below. This immediately aroused the interest of research scientists. However, in order to uncover the secrets of life from the deep sea, research scientists require the support of state-of-the-art technology, such as submersibles, equipped with lights, cameras and scientific equipment that can withstand the extreme pressure. This is the reason deep-sea research didn’t really gain momentum until the middle of the last century.

Scientists at the Alfred Wegener Institute Helmholtz Centrefor Polar and Marine Research in Bremerhaven (AWI) are highly interested in the impact of climate change on the deep-sea habitat. So that they can observe and understand the respective repercussions, long-term measurements are necessary. Since 1999, AWI has been operating the deep-sea observatory HAUSGARTEN in the eastern Fram Strait. In the area between Greenland and Spitzbergen, various physical and biochemical parameters are measured all year long at, in the meantime, 21 stations that are 1,000 to 5,500 metres deep. The scientists are on site every summer and take samples with different equipment in the water columns and on the seabed. In this year as well, they will spend almost four weeks over their “garden” with the research ship “Polarstern”. During the rest of the year the measuring devices, anchored on the seabed, deliver data non-stop.

In the meantime, the long-term observatory provides many indispensable results concerning the scarcely-explored deep sea and its inhabitants. Researchers are hence aware that climate changes on the ocean’s surface have an impact on the seabed ecosystem without a big delay in time. The images that the special cameras are delivering also unfortunately show us that plastic waste is increasingly accumulating in the deep sea. In 2002, plastic waste could be observed in about one percent of the images, while in 2011 it had already grown to two percent.

You might also like:

Natural resources: Mining in the deep ocean

Waste in the Ocean: The Plastic Plague

You can access all archived editions of HELMHOLTZ extreme here: www.helmholtz.de/extreme

Readers comments