Interview

How dangerous is the new coronavirus?

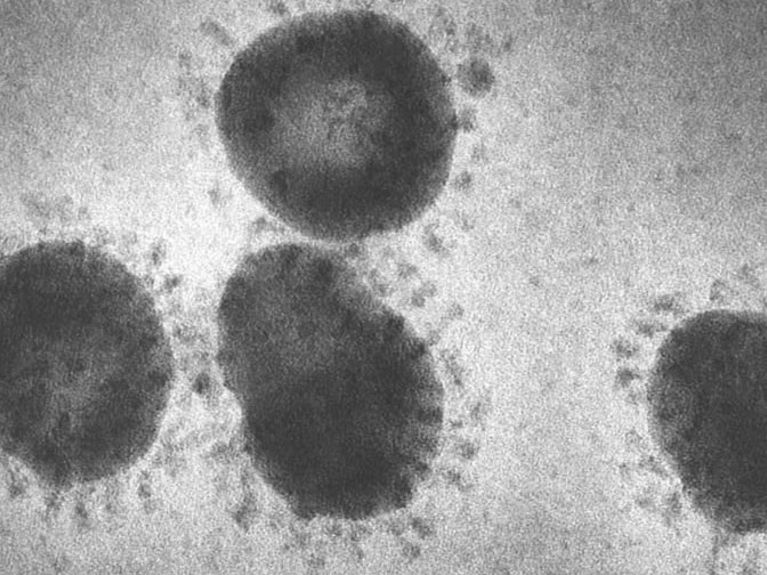

Coronaviruses under an electron microscope. Image: HZI

Infection researcher Luka Cicin-Sain from the Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research in Braunschweig discusses what we know so far about the novel coronavirus that originated in China, how dangerous it is, and what’s crucial now.

Interview with virologist Luka Cicin-Sain on February 18:

We are currently witnessing surreal scenes in China: Streets are deserted in metropolitan areas that are usually overcrowded; the city of Wuhan and several of its neighbors are under lockdown, putting more than 40 million people – equivalent to half of Germany’s population – under quarantine. And this is all due to what’s being called a novel coronavirus. Why is China taking such drastic measures? Is the virus really that dangerous?

There are many indications that the new coronavirus, which experts are also referring to as SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) coronavirus, is far less dangerous than the virus that emerged in 2003 and caused severe acute respiratory syndrome at the time. SARS had a mortality rate of around 10 percent – in other words, every tenth person who was infected with it died on average. And in the case of MERS, another coronavirus that appeared in 2012, the rate was actually 37 percent. The current numbers of infections and deaths caused by the novel coronavirus suggest that it has a mortality rate of around two percent. But I could easily see the rate being much lower.

What makes you think that?

We don’t really know how many people are actually infected with the novel coronavirus. In many cases, the virus causes hardly any symptoms, and many epidemiologists estimate that several hundred thousand people in China are affected by COVID-19. If you factor this into the number of deaths, the mortality rate would be significantly less than one percent. But these are just assumptions for now.

What do we know for sure about the novel coronavirus?

Prof. Dr. Luka Cicin-Sain is an infection researcher at the Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research in Braunschweig and is head of the Immune Aging and Chronic Infections working group there. Image: HZI/jab

We know the structure of the virus; its genome was already sequenced a couple of weeks ago! The virus is a member of the coronavirus family, as its name suggests. These viruses have been given this name because they look like they are encircled by a crown, or “corona”, which is the Latin word, when viewed under an electron microscope. Coronaviruses that infect humans have always existed. Between 10 and 15 percent of all colds that people tend to get in the winter can be attributed to members of the coronavirus family. These cold viruses are usually harmless because they are adapted to humans. But this isn’t the case with the novel coronavirus, which has only recently jumped from an animal to humans. Viruses tend to undergo mutations particularly frequently in such a new environment.

What impacts could mutations have?

Mutations are alterations in the genetic material that occur continually in every living creature and every time cells divide. They are what drives evolution. If an alteration is advantageous, the organism goes on living for longer and tends to spread. If an alteration is detrimental, it doesn’t become established. It works the same way with viruses. In many cases, a virus can’t replicate or spread all that effectively in a new environment, but advantageous mutations can accelerate the spread, and mutated viruses are favored.

Can mutations make coronavirus more dangerous?

In theory, yes. It’s important to distinguish between two terms here: infectiousness and virulence. Infectiousness is a virus’s ability to spread and infect more people. Virulence is its capacity to make people sick. But virulence depends on many different factors. As I said, there are people who exhibit hardly any symptoms, while it can be deadly for others. Mutations that cause more severe illness and higher mortality rates can of course occur. But this isn’t really advantageous for the virus, because a high level of virulence usually prevents the virus from going undetected while it spreads widely. Mutations that make the virus more contagious, on the other hand, are entirely likely. And when many, many people contract the virus, this is a problem, even if the virus only makes a small percentage of those infected extremely ill.

So, the problem right now isn’t so much the death rate as the infectiousness, or how contagious the virus is?

Exactly, and this tendency has become increasingly clear over the past few weeks. That’s why China has taken such drastic measures and placed entire cities under quarantine. They recognized that the virus is obviously more contagious than was initially assumed and then took massive steps to contain it. The question of whether all the measures are reasonable and proportionate is open to dispute. But we’re seeing some successes, because a majority of the cases of the virus have occurred in Wuhan and the surrounding area so far; that is, in the quarantine zone.

Even so, several hundred more infections are emerging every day in the rest of China as well. But there still have only been isolated cases in the rest of the world – for now. What will happen if the virus does manage to spread beyond China on a sustained basis?

Right now, we’re dealing with an epidemic. This is, by definition, the spread of a pathogen within a region – primarily in Wuhan and the surrounding area, but also in the rest of China. But if a virus is no longer limited to a region and spreads throughout the world, it’s referred to as a pandemic. The novel coronavirus isn’t causing a pandemic yet, but it’s entirely possible that it could still become one.

What would be the consequences of that?

An epidemic sounds dangerous when you hear it at first, and it’s often conveyed that way in the media as well. But an epidemic can also be relatively harmless. The influenza we saw in 2009, which was also known as swine flu, was a pandemic, but the infection took a relatively mild course. In other words, the number of people infected isn’t a reliable measure of the danger presented by a pandemic. There are even types of viruses that are endemic, which means they are continually circulating among us. A number of viruses from the herpes virus family, such as the Eppstein-Barr virus and the cytomegalovirus, infect around 90 percent of all people worldwide and stay in our bodies throughout our lives. Most of us aren’t aware of this because we never become sick. Only a

few people have symptoms, such as infectious mononucleosis, and suffer from fever, a sore throat, and fatigue. So, you could say that herpes viruses have also managed to spread to such an enormous extent because they mostly go unnoticed and are harmless in a vast majority of cases. There’s a peaceful coexistence between the host and virus in a sense, because the virus and the host have adapted to one another over millions of years. But we’re not well adapted to coronavirus, and it appears that it’s not entirely harmless at a minimum.

What are the key factors in successfully containing the spread of a virus?

You could say the key factors are comparable to efforts to contain a fire. You have to deprive the fire of oxygen and flammable material so it gradually goes out. In terms of the virus, this means that you have to deprive the virus of new hosts. So, people who are infected have to be isolated from those who are healthy. This depends on the condition of detecting people who are infected quickly and early on, so they can be isolated.

Will testing and the precautionary measures being carried out at airports be enough to prevent a pandemic?

The odds aren’t bad, but it could well be that the situation still develops into a pandemic. This isn’t set in stone yet and depends on a wide range of factors, both in terms of the biology of the virus as well as hygiene measures and how consistently they are implemented.

What is the risk of the virus spreading here within Germany?

People are very vigilant in Germany, all our doctors have the information they need, and suspected cases are quickly detected and tested. This means the risk of the virus spreading in Germany is significantly less than it is in countries with less developed healthcare systems.

What can we as individuals do to protect ourselves and further decrease the risk?

Wearing a face mask definitely isn’t a must in Germany at the moment. But I’d recommend frequent hand washing and sneezing into your elbow. This doesn’t just protect against infection with the novel coronavirus, which is still extremely unlikely in Germany right now. It also protects you against the much more likely eventuality of catching cold viruses or the flu.

Spread of COVID-19 broken down by federal states

The Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association has used data from the Robert Koch Institute (RKI) as the basis for developing a tool that shows the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases in Germany’s individual federal states.

Update from March 16: SARS-CoV-2 has continued to spread recently. The World Health Organization has now classified the outbreak as a pandemic. This means the virus is spreading on a broader scale across multiple countries and continents around the world. Cases of the infection continue to rise in Germany as well and have been confirmed in all of Germany’s federal states. Federal Minister of Health Jens Spahn stresses that it’s now essential to slow the spread of the disease to prevent the healthcare system from being overwhelmed. The question of how dangerous the virus is has yet to be definitively answered. What is clear is that it spreads extremely easily, which means it’s highly contagious. The Robert Koch Institute (RKI) currently assumes that a majority of cases tend to be mild. RKI President Lothar H. Wieler mentioned a figure of around 80 percent. He noted that 15 percent of cases are severe and estimated that the mortality rate is between one and two percent, based on the knowledge that is currently available. The likelihood of dying from influenza is 0.1 to 0.2 percent. That said, the mortality rate of SARS-CoV-2 is based on the number of cases that have actually been confirmed via testing. We can assume that there are more infections than are confirmed by tests. However, it will only be possible to reliably determine the actual rate once the pandemic is over.

Readers comments