Underwater observatory

The mystery of Boknis Eck

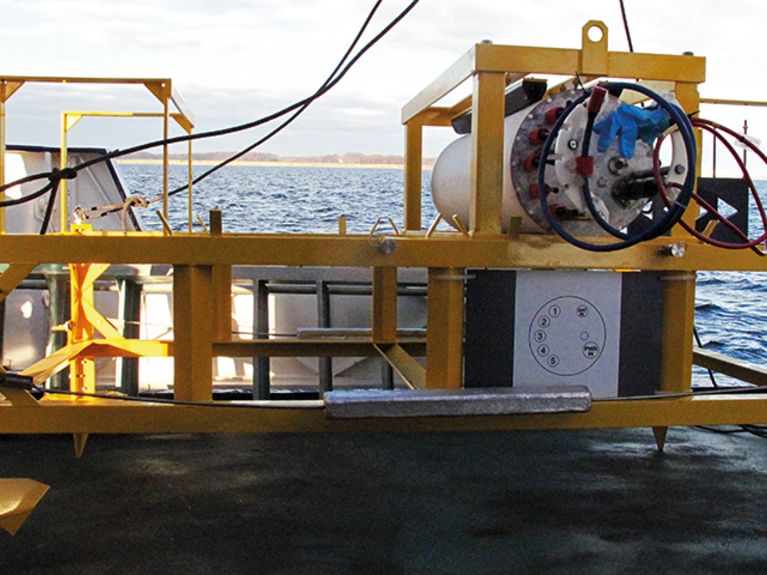

Vanished—the observatory sensors at Boknis Eck provided vital data for detecting changes in marine ecosystems. Image: University of Kiel Research Center

An underwater station installed by GEOMAR in Eckernförde Bay at a depth of 14.5 meters had been reliably transmitting data to the Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research in Kiel for many years. But it suddenly vanished without a trace—leaving researchers, specialist divers, and criminal investigators grappling with a mystery.

The day Boknis Eck’s core structure disappeared wasn’t a stormy one. There weren’t any naval vessels in the area, either above or below the water’s surface. No fishing boats had sailed through the restricted area on the Baltic Sea coast at the mouth of Eckernförde Bay, formed when a 17-kilometer-long glacier’s tongue penetrated deep into the land during the last ice age over 100,000 years ago. Everything was calm and quiet on the summer morning of August 21st when the observatory suddenly stopped transmitting data at 8:15 am.

Boknis Eck is a name that is known to researchers around the world. Basic data relating to the marine ecosystem has been collected in Eckernförde Bay two kilometers off the coast since 1957. Each month, researchers from the GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel measure salinity, temperature, and concentrations of oxygen, nutrients, and chlorophyll as well as climate-relevant trace gases like nitrous oxide and methane. In 2016, the researchers from Kiel teamed up with Helmholtz-Zentrum Geesthacht Center for Materials and Coastal Research (HZG) to add the Boknis Eck node to their old measuring station. This underwater observatory used a fiber optic cable to transmit its results to a station on land in real time—a key step in terms of supplementing the data they were measuring.

“It’s not actually a problem with the connectors. The station is basically gone!”

“A connection has probably come loose again,” thought project manager Hermann Bange when the researchers suddenly lost contact with the observatory. Bange, a professor of marine biogeochemistry, has been coordinating the team’s work at Boknis Eck since 2010 and oversaw the station’s construction. He contacted the research divers at the University of Kiel and asked them to check the connections, which are prone to damage under water. A week later, the Littorina research vessel made its way to geographic coordinates 54°31.2' N, 10°02.5' E. Four research divers went into the water expecting to carry out maintenance on the sensors. But they discovered something completely different. “It’s not actually a problem with the connectors,” declared Roland Friedrich, the training manager at the University of Kiel’s research diving center: “The station is basically gone!” Visibility is very limited here at a depth of nearly 15 meters, and the divers could only see 20 centimeters in front of them. They searched the surrounding area—and found nothing.

Researcher Hermann Bange couldn’t believe the photographic evidence the divers showed him. The cables were torn out, and two frames for the underwater observatory, which is worth 300,000 euros, were missing. Weighing 770 kilograms in total, the two elements that had disappeared were equipped with a wide range of high-end sensors. The researchers never believed that the station could simply disappear. It was sunk into the seabed, firmly anchored, and weighed as much as a small car.

The Boknis Eck node was installed at the beginning of 2017 to continuously record measured values. Image: University of Kiel Research Center

“We quickly realized what the loss of the observatory meant to us,” says Bange. His first thought was the many master’s theses that couldn’t be written now. Then he thought of the repercussions for the team’s work as a whole. “A continuous measurement system depends on continuous measurements” he says with resignation. The station was part of the Coastal Observing System for Northern and Arctic Seas (COSYNA), an integrated observation and modeling system coordinated by HZG that describes the environmental status of coastal waters in the North Sea and the Arctic. COSYNA provides authorities with data that is intended to support the planning of routine tasks such as coastal protection measures and preparing for emergencies. The observatory’s disappearance represents the loss of a key element for the system.

Boknis Eck’s location is ideal for research purposes. It offers insight into a coastal ecosystem influenced by distinctive changes in its salinity and the oxygen depletion that occurs when bacteria decompose organic material. The observatory was equipped with state-of-the-art sensors. How much oxygen is available to organisms in seawater? What nutrients are dissolved in the water? How rapidly are plankton growing? Answers to these questions allow researchers to draw conclusions about the state of the marine ecosystem. “The continuous measurements complemented the monthly time series perfectly, and we used them to establish entirely new connections between the data,” explains Bange. Analyses had shown that many events, such as brief hot spells or severe individual storms, that leave traces in the ecosystem could not have been recorded based on the monthly measurements. The researchers had invested two years of planning and construction work into the station before installing it in December 2016.

“The Boknis Eck dataset was in high demand internationally, too. It’s a shame that there will be such a big gap in the data now.”

Could a large fish have pulled away the frames? Out of the question; they were much too heavy. Extreme currents aren’t a possibility either. Nor are storms—there was calm summer weather that day, and the observatory had previously withstood severe storms without being damaged. Does that mean it was stolen? The researchers reported the incident, asked the water police for help, and criminal investigators launched an investigation. Newspaper articles were published, and there was an appeal for public assistance: Did anyone see boats in the restricted area? A campsite two kilometers away on land with a beautiful view of the sea attracts campers. But no one saw anything suspicious on the water that morning.

The police don’t have any leads. “We haven’t found anything yet,” says Sönke Hinrichs of the Neumünster Police Directorate, which is in charge of the investigation. There are no clues as to where the observatory might be. “The investigation hasn’t uncovered any further suspicious circumstances so far.” The German Navy has a torpedo range in Eckernförde Bay, and the First Submarine Squadron as well as fleet service vessels are also stationed there. So could one of the Navy’s vessels or even a submarine have accidentally rammed into the station and dragged it along with it? Senior Chief Petty Officer Maria Hagemann, Spokesperson for the German Navy, says: “We checked everything—none of our submarines or vessels were in the area that day.”

All that remained was a frayed shore cable. Image: University of Kiel Research Center

According to ship movement data, not a single ship was sailing near Boknis Eck at the time in question. This data is collected at sea using the AIS system (Automatic Identification System). But if a ship’s captain doesn’t want to be detected, they can simply switch off the transmitter that must be installed on any ship over 20 meters in length, essentially making it invisible. The solution to the mystery is believed to be a trawler that was secretly fishing illegally in the restricted area. Trawls are made of funnel-shaped nets that collect shoaling fish such as herring, cod, pollock, sprats, and mackerel. Bottom trawls are even dragged along the bottom to churn up the seabed and flush out plaice. Some of the nets are as long as 1.5 kilometers. Trawlers are criticized for using modern locating technology like sonar to specifically locate shoals and systematically fishing the waters to the point of exhaustion. They don’t mind if large by-catches get caught up in the process—so an underwater observatory wouldn’t even be noticed at first.

What upsets Bange most is the data. “The Boknis Eck dataset was in high demand internationally, too,” he says, “and it’s a shame that there will be such a big gap in the data now.” The small section of the observatory that remained intact is equipped with sensors for measuring fluorescence and chlorophyll and may be reconnected in the near future—provided the damage to the cable isn’t too extensive. But the longer it lies exposed on the seabed, the more unlikely this becomes. “The effort involved in laying the cable again is enormous,” stresses Bange. “Rebuilding the entire station will take around a year. We can only hope that the insurance covers a large part of the costs.”

The diving team from the University of Kiel recently boarded a research vessel to search the seabed with multibeam sonar. This high-resolution sonar maps the ground structure of the seabed—and revealed a 360-meter-long sliding mark. Based on this, the divers were able to identify two areas where the remains of the measuring station may be located. So Bange is pinning his last hopes on upcoming dives. But diving trainer Friedrich is concerned about the lack of visibility. “If your visibility is limited to 20 to 30 centimeters, a radius of just 10 to 20 square meters is a huge area to search.” Nonetheless, Bange sees plenty to hope for in this radius.

Boknis Eck: research since 1957

The name Boknis Eck has a worldwide reputation in marine research. Environmental data such as temperature, salinity, and nutrient content, oxygen and chlorophyll are regularly recorded here, enabling researchers to draw conclusions about the state of the southwestern Baltic Sea. Data has been collected here since 1957, making the Boknis Eck dataset one of the world’s oldest marine science time series still being recorded.

Readers comments